Abstract: I propose that our current Words of Mormon in the Book of Mormon was originally a second chapter of the book of Mosiah following an initial chapter that was part of the lost 116 pages. When Joseph Smith gave the first 116 pages to Martin Harris, he may have retained a segment of the original manuscript that contained our Words of Mormon, consistent with the Lord’s reference “that which you have translated, which you have retained” (D&C 10:41). A comprehensive review of contextual information indicates that the chapter we call Words of Mormon may actually be the first part of this retained segment.

In Section 10 of the Doctrine and Covenants, the Lord uses the term “that which you have translated, which you have retained” (D&C 10:41) as he provides a solution to the problem caused by the loss of the 116-page manuscript. The Lord’s solution is to replace the lost text with the small- plate record, followed by the balance of the translation, beginning with “that which you have translated, which you have retained.” I propose that this term refers to a segment of text translated before the loss but retained by Joseph Smith and that Words of Mormon, the text that now follows the replacement small-plate record, is the first part of this retained text. In other words, Words of Mormon once followed immediately after the lost text. It is the earliest part, still in existence, of Joseph Smith’s translation of Mormon’s abridgment of the large-plate record.

My paper begins by putting this proposal in the context of the scholarly landscape for the order of Book of Mormon translation. It then reviews historical information about the lost manuscript, the rest of the original manuscript, and the printer’s manuscript. After this review, it walks through six considerations which support a conclusion that the retained text — the segment of text that once followed immediately after [Page 2]the lost text — begins with Words of Mormon. First, traces of evidence, including four edits made by Oliver Cowdery to the printer’s manuscript, support the premise that Joseph Smith held back previously translated pages that weren’t lost. Second, a structured comment (a resumptive structure) found in Words of Mormon 1:9–10 indicates that a large block of Mormon’s abridgment of the large-plate record (the lost text) is missing right before the beginning of Words of Mormon. Third, a part of this resumptive structure indicates that the last event mentioned in the lost text once supplied foundational context for the aside in Words of Mormon 1:1–8, including antecedents for the terms this king Benjamin, these plates, and this small account in Words of Mormon 1:3. Fourth, textual analysis of Words of Mormon 1:3–6 suggests that Mormon wrote Words of Mormon before he wrote the following part of his abridgment. Fifth, linguistic analysis indicates that the term about to in Words of Mormon 1:1 can be read to support this conclusion. Sixth, the simple directives in Section 10 support my view that the retained text begins with Words of Mormon.

The Scholarly Landscape for

the Order of Book of Mormon Translation

Over the years, a variety of views have been expressed about the order in which the books of the Book of Mormon were translated.1 In recent decades, most scholars have adopted a Mosiah-first view, holding that when translation resumed after the loss of the 116 pages, it began at the beginning of the Book of Mosiah, then continued from there through the balance of the writings of Mormon and Moroni, including the title page. These scholars believe that the small-plate record was translated next, ending with Words of Mormon.2 In 2012, Jack M. Lyon and [Page 3]Kent R. Minson published a modified Mosiah-first view which suggested that verses 12–18 of Words of Mormon were originally part of the book of Mosiah, so these verses were translated first. They agree that the balance of the translation took place in the order described above, ending with verses 1–11 of Words of Mormon.3

This paper suggests that the entire chapter we call Words of Mormon is the original second chapter of the book of Mosiah. This entire chapter and some of the next chapter (which is now subdivided into Mosiah chapters 1–3) were translated before the loss of the 116 pages and retained by Joseph Smith. When translation resumed, it began at the end of this retained segment, continuing through the balance of the writings of Mormon and Moroni and then through the small-plate record, ending with the book of Omni. In a nutshell, I propose an expanded Mosiah-first view. Words of Mormon, in its entirety, is the original second chapter of Mosiah.

Historical Background:

The Lost Manuscript, the Rest of the Original Manuscript, and the Printer’s Manuscript

Joseph Smith began to translate the ancient Nephite record by “the gift and power of God” in April 1828 in Harmony, Pennsylvania. Joseph’s wife Emma served as his initial scribe.4 Soon, Martin Harris replaced Emma as the principal scribe. Book of Mormon manuscripts weren’t transcribed onto loose sheets of paper. Instead, several sheets of paper (usually about six of them) were folded together, once down the middle, to form a simple booklet called a gathering, so each gathering contained [Page 4]about 24 pages. After a gathering was filled with writing, it was stitched together at the fold.5

After two months of translation, in mid-June 1828, it appears that the translation filled five gatherings, four with six sheets (24 pages each) and apparently one gathering with five sheets (20 pages), for a total of 116 pages, as Royal Skousen has proposed,6 as well as some additional pages in an incomplete sixth gathering not given to Martin Harris.7 If so, the term that which you have translated, which you have retained may refer to these pages in this incomplete gathering — a gathering in process that wasn’t yet ready to be stitched together.8At this point, Joseph paused the work of translation to care for Emma, who was about to give birth.9

As the work of translation neared this stopping point, Martin planned to spend a few days at his home in Palmyra, New York. As that day approached, he repeatedly asked for permission to take along the completed manuscript to show it to certain family members. With each request, Joseph prayed for direction. Twice the answer was no. After a third petition, however, the Lord no longer denied the request.10 Although Joseph let Martin take 116 pages of manuscript (probably all completed gatherings), I assert that Joseph retained some translated [Page 5]text in an incomplete gathering (see Doctrine and Covenants 10:41), consistent with Lyon and Milton’s proposal.

About a day after Martin left, Emma gave birth to a son who was either stillborn or died shortly after birth. Joseph cared for a very weak Emma beyond the date when Martin was to return with the manuscript. In early July, as Emma recovered, and with her encouragement, Joseph went to his parents’ home in Manchester, New York (near Palmyra), where he learned that the 116-page manuscript was lost. He then returned to Emma in Harmony, Pennsylvania.11

Later that month (July 1828), Joseph received the revelation in Section 3 of the Doctrine and Covenants. In it, the Lord explains that because of Joseph’s error, he has lost the privilege of translation for a season, but if he will repent, he will be able to translate again.

After the loss, Joseph Smith wondered whether, when he eventually reached the end of the record, he should retranslate the lost portion. The Lord answered this question in the revelation published as Section 10 of the Doctrine and Covenants. It is not clear, however, whether this revelation was received shortly after the loss in 1828, after translation had resumed in 1829, or a combination of both. The heading for Section 10 says that it was given “likely around April 1829, though portions may have been received as early as the summer of 1828.” The editors for the Joseph Smith Papers Project note that “assigning a date to this revelation is problematic” and suggest that “although [Joseph Smith] may have received the first portion of the revelation in the summer of 1828, it was not actually written down until April or May 1829, along with the rest of the text.”12

In this revelation, the Lord explains that the lost portion of the manuscript is not to be retranslated (see D&C 10:30). Rather, the Lord reminds Joseph that the lost manuscript mentioned a separate account, written on the small plates13 of Nephi. Rather than retranslating the lost [Page 6]portion, the Lord directs Joseph to “translate the engravings which are on the [small] plates of Nephi down even till you come to the reign of king Benjamin, or until you come to that which you have translated, which you have retained” (D&C 10:41). Thus the small-plate account, which would be translated last, would become the “first part” (D&C 10:45)14 of the Book of Mormon.

The privilege to translate was eventually restored, and no later than March 1829, Joseph resumed the translation.15 The evidence, including textual analysis and historical sources, indicates that the translation [Page 7]resumed right where it had left off.16 If, as my paper asserts, Joseph had retained an incomplete gathering, with several translated pages and some blank pages, which retained text became the beginning of the original manuscript, the first post-loss entry was written on the very next line of that incomplete gathering. Little new translation occurred, however, until Oliver Cowdery took over as scribe on April 7, 1829.17

To obey the revelation in Section 10 of the Doctrine and Covenants, Joseph Smith continued translating the writings of Mormon and Moroni, and then translated the small-plate record. The Lord had explained that the small-plate record, which was translated last, would replace the lost text, which was translated first. Consequently, page numbering was restarted as the original manuscript continued with the small- plate record.18 The entire original manuscript was completed by June 30, 1829.19 Both the printer’s manuscript and the Book of Mormon are assembled in the order designated by the Lord, which differs from the order in which the original manuscript was received. Both the printer’s manuscript and the 1830 Book of Mormon begin with the title page and a preface, followed by the small-plate account. In all editions of the Book of Mormon, the small-plate account is followed by the retained text, which is, in turn, followed by the balance of Mormon’s writings and the writings of Moroni.

A portion of the original manuscript and virtually all of the printer’s manuscript still exist today:

Joseph Smith preserved both the original manuscript and the printer’s manuscript, or second copy, well past the publication of the Book of Mormon in 1830. He placed the original manuscript in the cornerstone of the Nauvoo House in 1841, [Page 8]and it was removed in 1882. Though significantly damaged, about thirty percent of this manuscript is extant, most of which is held at the Church History Library. The printer’s manuscript was in Oliver Cowdery’s custody until his death in 1850, followed by David Whitmer’s custody until his death in 1888. It was eventually sold to the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints and is held at the Community of Christ Library-Archives.20

Page numbers are found on extant pages of both the original and printer’s manuscripts. Royal Skousen notes, “In the original manuscript, Oliver Cowdery seems to have always written the page number in the upper corner of each page and on the outer edge of the page. (He also followed this same placement of the page number in the printer’s manuscript.)”21 In the Joseph Smith Papers, the Source Note for the printer’s manuscript indicates that each page of the printer’s manuscript was paginated except for the two introductory pages and the first leaf. “[Oliver] Cowdery numbered his pages on the upper right corner of the recto pages and the upper left corner of the verso pages. Hyrum Smith and [another scribe] paginated in the upper left corners for both recto and verso pages.”22

Despite the loss of much of the original manuscript, Skousen believes the consistent numbering of extant pages makes it safe to assume that other pages were numbered as well:

Unfortunately, there are no extant page numbers in the original manuscript for the translation of the plates of Mormon and Moroni (from the lost book of Lehi through the book of Moroni). In each case where part of a page is extant, the upper outer corner is missing. The upper inner (or gutter) corner of the page is generally extant for fragments from Alma, but in each extant instance Oliver Cowdery did [Page 9]not write the page number near the gutter. It is nonetheless safe to assume that these pages were numbered since evidence elsewhere consistently supports this practice. For instance, Joseph Smith knew there were 116 pages of lost manuscript (the book of Lehi), which implies that his scribes had been numbering the pages as they wrote down his dictation. …

There are extant page numbers for the translation of the small plates of Nephi (1 Nephi through Omni). … These small plates were probably translated last — that is, after the plates of Mormon and Moroni were translated. For the small plates of Nephi, the page numbers were sometimes extant (or partially extant). When extant, these numbers are always located in the upper outer corner of the page.23

In the original manuscript, there are extant page numbers (written by three different scribes) for pages 5–7, 11–18, 20, 22, 44, and 111–14.24

1. Evidence for a Retained Segment of Translated Text

That Wasn’t Lent to Martin Harris

It has been suggested that if the portion of Section 10 containing the word retained was received in 1829, then no evidence supports the view that translated text was held back at the time of the loss.25 It is true that most of the physical evidence that might support this view is no longer available. The lost manuscript was never recovered, and the original manuscript pages that contained the book of Omni, the words of Mormon,26 and the book of Mosiah were later lost to water damage. Nevertheless, traces of supporting evidence can still be gleaned from the extant manuscripts and revelations. While the extant evidence may not be conclusive, it supports a plausible case that Joseph Smith retained a segment of translated text at the time of the loss. I review three items of evidence.

The first is circumstantial but reasonable. The circumstances suggest that Joseph Smith was confident that exactly 116 pages were lost. A page number on the first retained manuscript page is a likely reason for this confidence. (Note, however, that it has recently been claimed that [Page 10]Joseph Smith’s published page count is inaccurate.27 Appendix A provides evidence to counter this claim.) The second set of evidence relates to the word retained in Doctrine and Covenants 10:41. Whether Joseph Smith received this part of the revelation in the summer of 1828 or after translation resumed, the context suggests that the word retained refers to translated text held back at the time of the loss. The third set of evidence is more significant. Four edits that Oliver Cowdery made to the printer’s manuscript lend additional support to the premise that Joseph Smith had held back previously translated text, including Words of Mormon.

Confidence in a Precise Number. Common sense suggests that manuscript pages are easier to manage when they are numbered. The evidence of page numbering across the extant manuscripts, together with the practical purpose for page numbers, suggests that Emma Smith and other scribes were numbering manuscript pages even before Martin Harris arrived in Harmony, Pennsylvania. Because virtually all extant manuscript pages are numbered, the assumption that the earliest manuscript pages were numbered may be less speculative than an assumption that they were not numbered.

Joseph Smith’s preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon was written to provide a true account of the lost manuscript. Before he wrote the preface, the Lord had warned him that “servants of Satan” (D&C 10:5) who had taken the lost manuscript sought to catch Joseph “in a lie, that they may destroy him” (D&C 10:25). The Lord warned that these “wicked men” (D&C 10:8) might use the lost manuscript (which the Lord suggests was still in their control) to discredit the published Book of Mormon. As Joseph drafted the preface, he would have expected those men to jump at the chance to prove that anything he published was a lie — perhaps including a bad guess about the length of the manuscript they now held. Therefore, Joseph arguably had good reason to avoid using an inaccurate page count that these wicked men might quickly prove to be false.

Because the Lord warned Joseph of their evil intentions, Joseph had several sensible options, but publishing an unverifiable, incorrect number wasn’t really one of them. If he had estimated his page count, he could have published it as such — using a round number or a range of numbers and a word like nearly or about, to avoid any appearance of lying. A clearly described estimate would have served his purposes [Page 11]as well as a specific number and would have avoided any claims that his published number was a lie. Nevertheless, the page count Joseph chose to publish to the world was very precise: “one hundred and sixteen pages.”28 The fact that Joseph published this precise page count under such circumstances suggests either that he was foolhardy or that he knew the page count was true. If Joseph had estimated his page count based on a whole number of gatherings each with six sheets of paper folded to have 24 pages, he would not have come up with 116 pages, since this number requires six gatherings, with one gathering having only five sheets. The number 116 seems unlikely to be the result of guesswork. Joseph Smith was not foolhardy. He was a responsible man of integrity who was confident that this page count was accurate. While there may be other explanations for such confidence, the simplest seems to be that Joseph still held several manuscript pages transcribed before the loss, and the first one had been numbered as page 117.29

The Context for the Word Retained. In Doctrine and Covenants 10:41, the Lord uses the term “that which you have translated, which you have retained.” This term refers to a segment of manuscript that was never lost. Opinions differ as to whether it refers to a segment translated before the loss, but retained (held back) rather than lost; or whether it refers to text that was newly translated months after the loss, and was thus retained (still possessed) weeks later at the time the revelation was written down.30

As explained earlier, it is not clear whether Doctrine and Covenants 10:41 was received in the summer of 1828 or in May or June of 1829. If it was received in 1828, nothing new had been translated since the loss, so the word retained must refer to text that was translated before the loss and held back. On the other hand, if it was received in 1829 after the translation had resumed, the context still suggests that the word retained refers to previously translated text that was held back at the time of the loss.

The word retained often refers to something kept in one’s own possession when something else is lost. It means “to keep in one’s own hands or under one’s own control; to keep back; to keep hold or [Page 12]possession of; to continue to have.”31 The following sentence tends to convey this meaning: Tom lost a baseball last week, but he’s now playing with the baseball he retained. To most readers, this sentence suggests that Tom initially had two baseballs. He lost one and is now playing with the other. The word retained carries this meaning when used in the context of a loss. If Tom had obtained the second baseball after losing the first, words like acquired thereafter or obtained later would convey this meaning better than the word retained.

The word retained appears to convey this same meaning in Section 10. In this revelation, the context clearly refers to something lost — the lost text — which the Lord repeatedly describes as translated words that have “gone out of your hands.” The terms include “the words which you have caused to be written, or which you have translated, which have gone out of your hands” (v. 10); “those words which have gone forth out of your hands” (v. 30); and “those things that you have written, which have gone out of your hands” (v. 38). Then, in contrast, the Lord refers to a different segment of text: “that which you have translated, which you have retained” (v. 41). In the context of a loss, the word retained doesn’t readily identify text that wasn’t translated until the work resumed several months after the loss. In this specific context, this word connotes a segment of translated text that was kept back at the time of the loss.

Four Items in the Printer’s Manuscript. Oliver Cowdery added four items to the printer’s manuscript that provide the best extant evidence that Joseph Smith held back previously translated text rather than lending everything to Martin Harris. These additions by Oliver Cowdery to the printer’s manuscript suggest that the original manuscript once held even better evidence of this retained text. Unfortunately, as explained above, 72 percent of the original manuscript was destroyed by water damage. The damage was unkind to the manuscript’s extremities. Neither its initial pages nor its final pages exist today.32 If both ends of the original manuscript were still available, there could be no confusion about whether Words of Mormon begins a segment of text held back by Joseph Smith, whether it was the first text translated after the loss, or whether it constitutes an addendum to the small-plate record. If Words of Mormon begins a segment of retained text that was translated before the loss, then it was written by Martin Harris and became the beginning text of the original manuscript. If it was the first text translated after the [Page 13]loss, it was not written by Martin Harris but became the beginning text of the original manuscript. On the other hand, if Words of Mormon were an addendum to the small- plate record, it would have been the final text at the very end of the original manuscript.

After the first 116 pages of original manuscript were lost, the truncated original manuscript began with “that which you have translated, which you have retained” (see D&C 10:41). If this retained text was translated and transcribed prior to the loss, it would have been the only (remaining) writing in the original manuscript in Martin Harris’s handwriting. If the pages containing this retained text were numbered by Martin Harris, then the original page number on the first of these pages was 117. In addition, this retained gathering may have been written on a different type of paper from that used in later parts of the manuscript. Paper was obtained “at fairly frequent intervals” during the translation process. “The original manuscript shows five different kinds of paper for extant pages,” so, in particular, the paper type used for this first gathering of the original manuscript (in June 1828) may have differed from that used more than a year later (in June 1829) for the final gathering of the original manuscript.33

The final gathering of the original manuscript — the gathering containing the final words of the small-plate record — would also have been unique. It appears that on earlier gatherings, every available line was used, and then the text flowed onto a subsequent gathering. However, it’s unlikely that the final words of the small-plate record — the last text translated from the gold plates — would have completely filled every line on every page of that final gathering. As a result, the last words on that unique gathering would likely have been followed by blank space, and perhaps by several blank pages (all remaining pages in that final gathering).

Thus, if Words of Mormon were written by Mormon at the end of the small-plate record, or on plates added to the small plates, it would have been the last text on that unique final gathering at the end of the original manuscript. It would also have been the last text translated by Joseph Smith. As such, in the original manuscript, it would likely have been followed by blank space, and perhaps by blank pages.34 On [Page 14]the other hand, if Words of Mormon is the beginning of a segment of text translated before the loss, but retained, it would also be the first (retained) text translated by Joseph Smith and would have been found at the beginning of the original manuscript. In addition, it would be written in Martin Harris’s handwriting, perhaps on a different type of paper than that used at the end of the original manuscript.

As Oliver Cowdery copied the text from the original manuscript to the printer’s manuscript, he would have known whether he copied Words of Mormon from the unique gathering at the very beginning of the original manuscript or from the other unique gathering at the very end. However, neither the first part nor the last part of the original manuscript exists today, so the printer’s manuscript, onto which the text of the original manuscript was copied, is our earliest source for the text from these two ends of the original manuscript. It is there where we must look for clues.

The most unique juncture in the printer’s manuscript may be the point where the very last words from the end of the original manuscript (the final words from the small-plate record) are followed by the very first words from the beginning of the original manuscript (the first words of the retained text). This point joins the first and last words from the original manuscript. It is also the point where the lost text would have ended had it not been lost.

Sadly, the decayed beginning and ending parts of the original manuscript removed most of the evidence that could help us identify this unique juncture. When Oliver Cowdery35 copied the words from these two (last, and then first) gatherings of the original manuscript onto the printer’s manuscript, their apparent meeting point fell in the middle of a page. For this reason, we might expect no evidence at all in the printer’s manuscript that designates the point where the original manuscript’s very last words are followed by the original manuscript’s very first words.

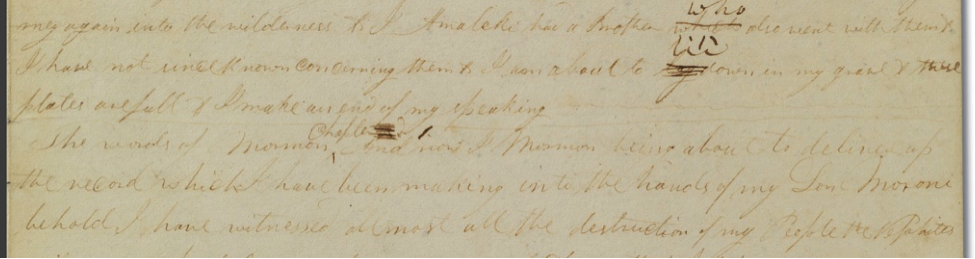

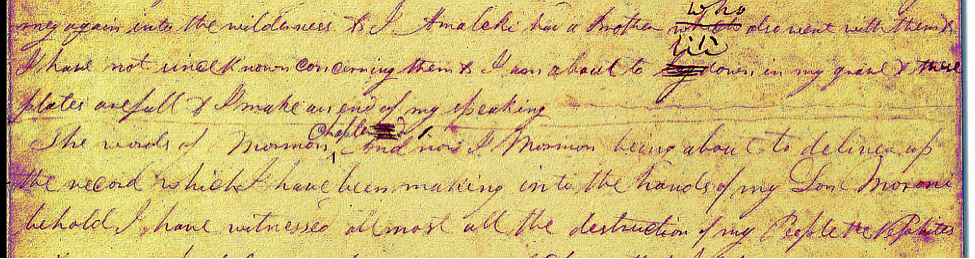

Providentially, however, Oliver Cowdery placed a unique mark (one that occurs only once in the entire printer’s manuscript) at the likely location of this pivotal point. In the printer’s manuscript, Amaleki’s last words in the book of Omni, “plates are full and I make an end of my speaking,” fill half a line. After these words, Oliver Cowdery drew a wavy line from the word speaking to the right edge of the page. He then drew a second wavy line all the way across the page before he resumed [Page 15]with “The words of Mormon and now I Mormon being about to deliver up” on the first line of text after the two consecutive drawn lines.36

Figure 1 shows an image of the applicable part of the printer’s manuscript, showing these two consecutive lines. Because these lines have dimmed with time, I’ve added a second, enhanced image in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Printer’s manuscript showing two lines.

Figure 2. Enhanced printer’s manuscript showing the same two lines.

Oliver Cowdery left no record to explain the purpose of this unique mark, consisting of two consecutive wavy lines, but it appears to identify a break that Oliver deemed both important and unique. It is a more prominent and conspicuous mark than anything Oliver or other scribes placed between successive books in the printer’s manuscript. The unique nature of this mark suggests that Oliver considered the break it designates to be significant. At the very least, we can infer that this mark at the end of the book of Omni indicates that Oliver knew the book of Omni didn’t extend beyond this point. Oliver’s mark appears immediately before the heading The words of Mormon. I assert that the intent of Oliver’s unique mark is to designate the precise point where the final, most recently translated words from the original manuscript (at the end of the replacement small-plate record) meet the first available, earliest translated words of the original manuscript (at the beginning of the retained gathering).37

[Page 16]Two out-of-place chapter numbers were originally found in the printer’s manuscript right after this mark, and both of these original chapter numbers were later edited by Oliver Cowdery. The first was the ordinal Arabic number 2d (second).38 It identified the chapter labeled “The words of Mormon.” The second was the Roman numeral III (three).39 It identified the subsequent chapter, which, in later editions of the Book of Mormon, has been subdivided into three chapters (Mosiah 1–3). The formatting of these two original chapter numbers in the printer’s manuscript (an ordinal Arabic number followed by a Roman numeral) can seem odd in our day, when we are used to the uniformity of word processors and automatic paragraph numbering. Unusual chapter numbering like this, however, is common in the printer’s manuscript. In [Page 17]1 Nephi, we find 2d followed by III.40 In 2 Nephi, we find 1st followed by II.41 And in Alma, we find 10th followed by XI.42

A likely reason for these two out-of-place chapter numbers in the printer’s manuscript becomes clear as we focus on their location (right after Oliver’s mark) and on the process by which chapter numbers were added to the original manuscript. Royal Skousen explains that the ancient record contained neither the word chapter nor chapter numbering:

Evidence from both the original and printer’s manuscripts shows that Joseph Smith apparently saw some visual indication at the end of a section that the section was ending. Although this may have been a symbol of some kind, a more likely possibility is that the last words of the section were followed by blankness. Recognizing that the section was ending, Joseph then told the scribe to write the word chapter, with the understanding that the appropriate number would be added later.43

It should be noted that the evidence supporting this description is found in the extant record left by Oliver Cowdery (and later scribes). The extant manuscripts contain many original samples of Oliver Cowdery’s chapter numbering. Skousen bases his specifics on these samples, which indicate that Oliver often left a blank space and the word chapter at the beginning of new chapters and that he sometimes waited a long time before adding the chapter numbers.44

On the other hand, the extant manuscripts provide almost no specifics on how Martin Harris may have added chapter numbers to the text he transcribed. One would surmise that the fundamental facts were the same. The ancient record didn’t contain chapter numbering, so Joseph would have indicated chapter breaks to Martin; and Martin would have at some point added chapter numbers into those breaks. However, all original chapter numbers supplied by Martin Harris are lost. Most were lost with the lost manuscript, and any chapter numbers that Martin added to the retained text have perished with the decayed original retained gathering. Therefore, we don’t have any original samples from which to infer the specific manner in which Martin added chapter numbers to the text he transcribed. There is no extant text from [Page 18]which to infer how quickly he added chapter numbers or even whether it was his practice to insert the word chapter with each chapter number. It appears that any differences in these specifics could apply to the two out-of-place chapter numbers because they appear to have been added to the original manuscript’s retained gathering by Martin Harris and later copied to the printer’s manuscript by Oliver Cowdery.

We can assume that while Martin Harris was the principal scribe for the earliest part of the manuscript, most of which became the lost manuscript, Martin had added text and chapter numbers to the original manuscript through the same basic editorial process that would later be used by Oliver Cowdery and others. Using this process, Martin transcribed most of the book of Lehi, all of which would soon be lost.45 As the translation continued, Joseph dictated the original title for the book of Mosiah and the text of its first chapter, which, it appears, were also soon lost. Royal Skousen suggests that the lost manuscript “included not only all of Lehi, but also part of Chapter 1 of the original Mosiah.”46 As explained in more detail below, this paper suggests that all of that original Chapter 1 was lost.

When Joseph indicated the end of that original first chapter of the book of Mosiah, it appears that Martin noted the chapter break either as the last item at the bottom of a page or as the first item at the top of the next page — the first page of a new gathering he would never complete — the retained gathering. The first page of this new original manuscript gathering was page 117. It began with the chapter heading “The words of Mormon” and continued with the text we know as Words of Mormon, which, based on the out-of-place chapter numbers and other evidence detailed below, appears to be the original second chapter of Mosiah. As the translation continued, Joseph indicated the end of this second chapter and translated some of the third chapter. Then, as Martin prepared to take the completed gatherings to Palmyra to show them to family members, he added any missing chapter numbers to the manuscript, including these last two chapter numbers, 2d and III, per the editorial process described by Skousen.

Martin then borrowed all completed gatherings. Unfortunately, those completed gatherings were stolen, but Joseph Smith retained the incomplete gathering that began (on page 117) with the heading “The [Page 19]words of Mormon.” When the lost manuscript was stolen, Joseph lost the power to translate for a time. When this power was restored, the work continued right where it had left off. The retained manuscript was completed, and the translation eventually proceeded through the balance of Mormon’s writings, through Moroni’s writings, and then the writings on the small plates, ending with the book of Omni.

After the original manuscript was finished, work began on the printer’s manuscript. After the title page and a preface written by Joseph Smith, it begins with the small-plate record — copied from the last part of the original manuscript. After Oliver Cowdery copied the final words from the book of Omni to the printer’s manuscript, he marked the end of the replacement small-plate text with two wavy lines.47 He then began copying from the retained gathering at the beginning of the truncated original manuscript. He faithfully copied the text of this retained gathering as it existed on the original manuscript. However, the lost text no longer preceded this retained text, so the two chapter numbers for this text were now out of place.

Oliver Cowdery added the word Chapter and the first of these chapter numbers (2d) as interlinear insertions, just beneath his distinctive mark. It appears from the ink flow that this interlinear insertion, like the interlinear insertion of the word as later on the same page, was made fairly soon after Oliver copied the accompanying text. Perhaps both were initially overlooked, then noticed and inserted. The reason for initially overlooking the chapter number may be as inadvertent as the reason [Page 20]for initially overlooking the word as, but there appear to be at least two other reasonable possibilities.

One might speculate that Martin Harris designated chapters slightly differently than Oliver Cowdery tended to do, so when Oliver encountered this first chapter number, he didn’t initially recognize it for what it was. Perhaps he wasn’t sure what to make of the (perhaps poorly formed) 2d at the top of the first retained manuscript page until he saw the III at the beginning of the next chapter. Perhaps at that point he realized that the earlier 2d was also a chapter number, so he went back and added the word Chapter and this number as interlinear insertions.

A second possibility is that the chapter number 2d wasn’t found at the top of the first page of the retained gathering. The first retained page may simply have begun with the heading “The words of Mormon.” The chapter number may have been the last item placed on the previous page (now lost), just as a chapter number is the last item found on page 163 of the printer’s manuscript.48 Perhaps Oliver realized (after having transcribed most of the original manuscript) that the chapter heading “The words of Mormon” necessarily started a new chapter. After he saw the III at the beginning of the next chapter, he knew which chapter number to insert, so he added Chapter 2d as an interlinear insertion after the heading “The words of Mormon.”

Sometime after Oliver Cowdery faithfully copied the text of the retained gathering, including these two chapter numbers, to the printer’s manuscript, he realized that edits were needed. Without the missing book title, all the text from Oliver’s mark to the start of the book of Alma was orphaned — it had no book title. In addition, these retained chapter numbers were out of place because they no longer followed a chapter 1. Probably after consulting with Joseph Smith, Oliver made three reconstructive edits. He chose to treat the original second chapter, with its heading “The words of Mormon,” as if it were an independent segment or book by changing its chapter number to 1.49 He also changed the chapter number for the original third chapter to I and added the book title “The Book of Mosiah” as an interlinear insertion at the head of this chapter.50 This book title, relocated from the lost text to this new location [Page 21]in a reconstructive edit, lacks the extended description of book contents that accompanies all other book titles in Mormon’s abridgment.51

Other context corroborates the fact that the original first chapter of Mosiah is missing. Mosiah is the only book in Mormon’s abridgment that doesn’t begin with an account about the person for whom it is named. The book of Alma begins with an account about Alma. The book of Helaman begins with an account about Helaman, and so on. The retained portion of the book of Mosiah, however, doesn’t begin with an account about the first King Mosiah. After Mormon’s aside, he resumes his ongoing account, which is about King Benjamin, the son of the first King Mosiah. Mormon’s abridged account about King Benjamin’s father, the first King Mosiah, is missing.52 It seems safe to infer that the missing original first chapter of Mosiah began with the account of the first King Mosiah.53

Oliver Cowdery made these reconstructive edits to his printer’s- manuscript copy of Martin Harris’s transcription from the retained gathering of the original manuscript. Oliver’s edits altered the original chapter numbers, but as we have seen, the numbers themselves were not part of the revealed text. His edits kept intact all known revealed text that had been retained, including the heading “The words of Mormon.” His reinserted book title “The Book of Mosiah” may have even restored a small sliver of revealed text that had been lost.54 Thus, Oliver’s edits provide some reconstructed structure for this remnant of text that is now bereft of the lost preceding text. As they do so, however, these edits also make it harder for readers to see that Mormon wrote the text we call Words of Mormon as the original second chapter of the book of Mosiah and not as an independent book.

Other explanations for the two out-of-place chapter numbers don’t accurately account for Oliver’s unique mark or for the way chapter numbers were originally added to the manuscript. The ancient record [Page 22]itself is not the direct source for any chapter number in the manuscript. The numbering came through the editorial process described above. Accordingly, if there were no retained text, a new translation from the ancient record after the entire earlier manuscript was lost would not have produced a number 2 or 3 as its initial chapter number.55 Joseph would have seen a visual indication that a prior section had ended. He would have told the scribe to write the word chapter, with the understanding that the appropriate number would be added later. With no prior number available due to the missing manuscript, the scribe would eventually have given the first new chapter the number 1, and there would have been less need for reconstructive edits. But the manuscript clearly contained two consecutive chapter numbers that seemed out of place. The best explanation for these two seemingly out-of-place chapter numbers right after Oliver Cowdery’s unusual mark is that they were added to the retained part of the original manuscript by Martin Harris and copied to the printer’s manuscript by Oliver Cowdery.

Another suggested explanation for these out-of-place chapter numbers is that one56 or both57 of them were mistakenly supplied by Oliver Cowdery, who may have wrongly believed that the corresponding text was a continuation of the book of Omni. In support of this suggestion, it has been proposed that “the seam between the small plates translation, Words of Mormon, and the beginning of Mosiah was no more clear for Oliver than it is for us.”58

But the construction of the original manuscript suggests that Oliver could not have shared that confusion. He was well acquainted with the original manuscript. He knew it began with the retained segment and ended with the final text from the small plates. Oliver’s mark in the printer’s manuscript right after Amaleki’s final words, “these plates are full and I make an end of my speaking” (Omni 1:30), appears to indicate Oliver’s personal certainty about the ending of Omni’s book. It seems unlikely that the person who inserted this substantial mark could have believed that the book of Omni continued after this mark. Oliver added both the word Chapter and the chapter number 2d as interlinear insertions just beneath his distinctive mark59 and just after the heading “The words of Mormon.” To insert the chapter number, Oliver had [Page 23]to focus on both his mark and this heading, which clearly identifies Mormon as the author of the following text. He would have known that the chapter number he was inserting belonged to the words of Mormon and not to the book of Omni.

Nor is it likely that Oliver mistook the next chapter (now Mosiah 1–3) for part of the book of Omni. In the first place, it too followed Omni’s final words, Oliver’s own obvious mark, and Mormon’s heading, “The words of Mormon.” Moreover, it’s likely Oliver had a unique affinity for this particular chapter. It appears that Oliver helped transcribe at least part of this lengthy chapter as he joined Joseph in the work of translation.60 So the very first words of Joseph Smith’s dictation Oliver transcribed after arriving in Harmony, Pennsylvania on April 7, 1829, would have been within this lengthy chapter. Oliver clearly knew this chapter, probably the first he helped transcribe, could not belong to the book of Omni, which was translated almost three months later in Fayette, New York.61

In summary, the idea that Oliver Cowdery inserted the original numbers for these two chapters under the mistaken belief that they continued the book of Omni strains credulity. Oliver’s own unique mark and his personal involvement with the transcription of the text both argue against that scenario. It seems more likely that everything that happened with these chapter numbers happened purposefully. First, Martin Harris, as Joseph Smith’s scribe, transcribed this portion of the original manuscript, assigning correct numbers to these chapters — the original second and third chapters of Mosiah. Then, all 116 pages of manuscript preceding this retained portion were lost. Eventually, after the translation was completed, Oliver Cowdery copied all the replacement small-plate record from the end of the original manuscript to the printer’s manuscript. He then marked the end of that record and copied this small retained segment of Martin Harris’s transcription, with its chapter number or numbers, from the beginning of the original manuscript to the printer’s manuscript. Sometime after that, Oliver Cowdery (most likely after consulting with Joseph Smith) found it necessary to edit these chapter numbers (and insert the book title for Mosiah) to mitigate problems caused by the absence of the lost text.

The heading “The words of Mormon,” which appears at the head of the original second chapter of Mosiah, is not a book title. It is one of the occasional chapter headings (brief descriptions) that sometimes [Page 24]introduce content within the books of the Book of Mormon. Because current Book of Mormon chapter divisions vary from those in the original text, some readers may not be aware that every such heading begins an original Book of Mormon chapter. Most original chapters don’t have such headings, but each such heading (which may describe only part of a chapter or may describe multiple chapters) appears at the head of an original chapter.

A list of all such occasional chapter headings in the Book of Mormon with their capitalization from the printer’s manuscript is included in Appendix B. The heading “The words of Mormon” appears to belong to this group of headings. It begins with the term the words, the most common term at the beginning of these headings. With only four words, “The words of Mormon” is the shortest of these headings, but there are several with six to nine words. Two factors in particular distinguish all these headings from all book titles in the Book of Mormon. First, none of these headings contains the word book, found in all book titles in the Book of Mormon. Second, in the printer’s manuscript, all book titles are written with title capitalization, so the word Book is always capitalized. On the other hand, in the printer’s manuscript, these occasional headings are not written with title capitalization, although, as Appendix B shows, some of them have nonstandard capitalized words and a few approach title capitalization. As a general rule, however, the words prophecy, account, words, etc., tend not to be capitalized in these headings.

The heading “The words of Mormon” appears to cover only part of the chapter it heads. Although Mormon wrote all the words in this chapter, the heading appears to refer only to Mormon’s personal aside, which is found only in verses 1–8. After this aside, the chapter continues as Mormon resumes his abridgment, covering various events of King Benjamin’s reign. Some of the other occasional headings also cover only part of a chapter. For instance, the heading “The prophesy of Samuel the Lamanite to the Nephites” refers only to the first part of the original chapter it heads. After relating Samuel’s prophesy, that chapter continues, covering four years of Nephite history that take place after Samuel leaves the land of the Nephites (see Helaman 13–16). Similarly, the heading “An account of the preaching of Aaron and Muloki and their brethren to the Lamanites” heads an original chapter that also covers some of the efforts of Ammon and King Lamoni and ends with an aside that describes Lamanite and Nephite lands (see Alma 21–22).

As explained earlier, Oliver Cowdery (probably in consultation with Joseph Smith) chose to leave the heading “The words of Mormon,” [Page 25]which is part of the revealed text, alone — neither replacing it with the book title “The Book of Mosiah” nor awkwardly inserting the book title immediately before this retained heading. Because Oliver changed the chapter number to 1, this heading has, ever since, been given title capitalization and has been formatted as a book title — further obscuring the fact that the chapter it heads is the original second chapter of Mosiah. The revealed text itself, however, which was not edited, together with Oliver Cowdery’s mark and edits to the printer’s manuscript, suggest that this heading begins the retained text — the earliest extant chapter of Mormon’s abridgment of the book of Mosiah.

2. Evidence from a Resumptive Structure Indicating that Words of Mormon Follows Immediately after the Text of the Lost Manuscript

A resumptive structure in Words of Mormon 1:9–10 provides further evidence for the view that Words of Mormon was not found at the end of the small-plate record, but is the first part of the retained text — the original second chapter of Mosiah. A detailed explanation of resumptive structures (specialized, structured comments) was given in a recent paper that suggests the location of Nephi’s abridgment of Lehi’s record.62 That paper explains how the consistent meaning inherent in resumptive structures weighs against one proffered location for the end of that abridgment. As explained in that paper, the resumptive structure is sometimes used by Nephi, Mormon, and Moroni to restart an ongoing narrative that has been paused for an aside (see, for example, 1 Nephi 10:1–2; Alma 22:35–23:1; and Ether 6:1–2, 9:1,63 and 13:1–2). Resumptive structures are used only a few times in the Book of Mormon, [Page 26]but when they are used, they always follow immediately after asides, and they are always composed of three elements:

- The first element always identifies the specific ongoing narrative that began long before the aside and is being resumed after the aside. The verb to proceed, when used in this element of a resumptive structure, always means to resume or continue.

- The second element always recaps the last event mentioned in that narrative before it was paused for the aside. This recap serves as the starting point for the resumed narrative.

- The third element is the resumption of the narrative, which always follows right after the recap of that last event as if there had been no aside.

The following two representative resumptive structures exemplify the functions of these three elements. In each case, for clarity, the first element is bolded; the second is italicized; and the beginning of the third (which always continues in subsequent verses) is underlined.

Moroni placed a representative resumptive structure immediately after his aside about faith (see Ether 12:6–41). This structured comment resumes his account of the destruction of the Jaredites:64

And now I Moroni proceed [continue] to finish my record concerning the destruction of the people of which I have been writing. For behold, they rejected all the words of Ether, for he truly told them of all things from the beginning of man.” (Ether 13:1–2)65

The first element of this resumptive structure explains that Moroni is resuming the ongoing narrative he had been writing about the destruction of the Jaredites (before he paused that narrative to write his aside). The second element recaps the last event mentioned in that narrative before the aside — that the Jaredites didn’t believe Ether’s words (see Ether 12:5). The third element resumes Moroni’s narrative as if there had been no aside.

[Page 27]As a second example, Nephi placed a representative resumptive structure immediately after his aside about his two sets of plates (see 1 Nephi 9:2–6). This structured comment resumes his account of his own reign and ministry:

And now I Nephi proceed [continue] to give an account upon these plates of my proceedings and my reign and ministry. Wherefore to proceed [continue] with mine account, I must speak somewhat of the things of my father and also of my brethren. For behold, it came to pass that after my father had made an end of speaking the words of his dream and also of exhorting them to all diligence, he spake unto them concerning the Jews. (1 Nephi 10:1–2)

In this resumptive structure, the first element explains that Nephi is resuming the ongoing narrative he had been writing about his ministry (before he paused that narrative to write his aside). The second element recaps the last event mentioned in that narrative before the aside — that Lehi finished speaking about his dream and other teachings (see 1 Nephi 8:36 to 9:1). The third element resumes Nephi’s narrative as if there had been no aside.66

Words of Mormon 1:9–10 is strikingly similar to the above two resumptive structures (and all others) in both context and content. Mormon placed this resumptive structure immediately after his aside about the record he is making and the small plates he has found (see Words of Mormon 1:1–8). This structured comment resumes the account he is taking from the large plates of Nephi:

And now I Mormon proceed [continue] to finish67 out my record which I take from the [large] plates of Nephi; and I make it according to the knowledge and the understanding which God hath given me. Wherefore it came to pass that after Amaleki had delivered up these plates into the hands of king [Page 28]Benjamin, he took them and put them with the other plates. (Words of Mormon 1:9–10, emphasis added)

This resumptive structure has the same three elements we find in all other resumptive structures. The first element explains that Mormon is resuming the ongoing narrative he had been abridging from the large plates of Nephi (before he paused that narrative to write his aside). In this case, however, all that narrative is missing from the Book of Mormon. The second element recaps the last event mentioned in the narrative before the aside — that Amaleki had delivered the small plates to King Benjamin (this does not occur in Omni, where Amaleki expresses only his intention in Omni 1:25 to later give the plates to King Benjamin, but the transfer of the plates is not recorded prior to Mormon’s mention of it as an accomplished fact). In this case, however, because the narrative is missing, the record of this event is no longer present before the aside. The third element should resume Mormon’s narrative as if there had been no aside, but all that narrative is missing, so this element begins the subsequent portion of Mormon’s abridged narrative — the only portion still present in the Book of Mormon.

Thus, this resumptive structure points quite precisely to a specific narrative, abridged by Mormon from the large-plate record, that is missing just before Words of Mormon. Mormon paused this narrative to write his aside. This missing narrative is the well-documented missing account that was transcribed, primarily by Martin Harris, onto the 116- page lost manuscript.

The resumptive structure places this missing account in a specific location that may surprise some students of the Book of Mormon (immediately before Words of Mormon). Without the information provided by this resumptive structure, few of us would have suggested that the heading “The words of Mormon” at the beginning of Mormon’s aside originally followed immediately after the text of the lost manuscript. Nevertheless, this location coincides with Oliver Cowdery’s mark, which was placed precisely at the point where this resumptive structure indicates the lost manuscript ended and the retained portion of Mormon’s abridgment begins. The correctness of this somewhat unexpected location is further corroborated by a solid set of relevant evidence detailed below.

Indeed, as we read Words of Mormon in light of the meaning inherent in the resumptive structure, its structural meaning gives new significance to several words and phrases in Words of Mormon. All words in Words of Mormon harmonize well with the meaning [Page 29]inherent in the resumptive structure. For example, the second element of a resumptive structure always recaps the last event mentioned in a narrative paused for an aside. In this case, this second element says “Amaleki had delivered up these plates into the hands of king Benjamin” (Words of Mormon 1:10), so the resumptive structure indicates that, in text now missing from the Book of Mormon, Mormon had discussed this delivery of the small plates just before he wrote the aside that begins with the heading “The words of Mormon.”

This now-missing discussion, written by Mormon, is reminiscent of a well-known passage in the small-plate record written by Amaleki. In that passage, Amaleki tells us he plans to deliver the small plates to King Benjamin: “knowing king Benjamin to be a just man before the Lord, wherefore I shall deliver up these plates unto him” (Omni 1:25). After mentioning this plan, Amaleki then continues his small-plate account by detailing gifts of the Spirit, inviting his readers to come unto Christ, and describing one group’s failed attempt to return to the land of Nephi, followed by another group’s presumably successful attempt. After adding all this information to his small-plate record, Amaleki simply concludes the small-plate record, with no mention of the actual delivery of these plates to King Benjamin.

It’s not surprising that the small-plate record doesn’t describe the actual delivery of the small plates to King Benjamin. In the first place, Amaleki had already filled the small plates, so there was no room for further explanation. In the second place, once these plates were delivered to King Benjamin, they were no longer in Amaleki’s possession, so we should expect any description of the delivery itself to be found in King Benjamin’s large-plate record. As mentioned earlier, the recap in the second element of the resumptive structure indicates that the large- plate record did, in fact, recount Amaleki’s actual delivery of the small plates to King Benjamin. Mormon included this event in his abridged record just before the aside in Words of Mormon 1:1–8. Unfortunately for us, Mormon’s original description of this event is now missing, but the recap in Words of Mormon 1:10 indicates that this was the final event described by Mormon in the lost text.

3. Foundational Context for Mormon’s Aside Provided by His Reference to a Passage That Was Lost

The aside preceding each resumptive structure in the Book of Mormon is itself prompted by the earlier discussion of the last event before the aside. The aside in 1 Nephi 9:2–6 follows an explanation that Lehi said many [Page 30]things that can’t be written on “these plates” (1 Nephi 9:1). This leads into Nephi’s aside about his two sets of plates. The aside in Alma 22:27–34 follows an explanation that the king send a proclamation “throughout all the land amongst all his people” (Alma 22:27). This leads into an aside about the lands of the Lamanites and of the Nephites. The aside in Ether 4:1 to 5:6 follows an explanation that the brother of Jared left the mount where he had seen the Lord and then wrote the things he had seen (see Ether 4:1). This leads into an aside about the subsequent history of what he wrote. The aside in Ether 8:20–26 follows an explanation that Jared, his daughter, and Akish formed a secret combination (see Ether 8:17–19). This leads into an aside that warns latter-day Gentiles about such combinations. The aside in Ether 12:6–41 follows an explanation that the people didn’t believe the great things Ether taught, because “they saw them not” (Ether 12:5). This leads into an aside about faith in things not seen.

In the case of Mormon’s aside in Words of Mormon 1:1–8, the resumptive structure (Words of Mormon 1:9–10) indicates that the last event discussed before the aside was Amaleki’s delivery of the small plates to King Benjamin. Even though this event no longer precedes the aside, it provides introductory context for the aside. In the aside itself, Mormon mentions searching for the small plates after working on his earlier abridgment. He doesn’t, however, specify what induced him to initiate the search (see Words of Mormon 1:3). The event he had described just before his aside appears to supply this context. According to the resumptive structure, shortly before searching for the small plates, Mormon had abridged the large-plate description of Amaleki’s delivery of these small plates to King Benjamin. Having thus learned of their existence, he searched for them, found them, and studied their engravings. As he did so, the Spirit touched him, which led him to write his aside about this spiritual experience. He added the chapter heading “The words of Mormon,” identified himself, and then recounted how this exciting find and the workings of the Spirit affected him. They evoked a determination not only to include the small plates with his own record but also to base the balance of his abridgment on the small- plate prophecies (see Words of Mormon 1:4–7). Mormon’s resumptive structure (Words of Mormon 1:9–10) then transitions readers back to his continuing abridgment of the large plates (with this new emphasis on these prophecies).

Early in his aside, Mormon refers to something that Amaleki had previously said about King Benjamin. Specifically, he refers to “this king Benjamin of which Amaleki spake” (Words of Mormon 1:3). [Page 31]Mormon’s words in this verse suggest this is not a reference to something written on the small plates. Just before this reference to King Benjamin and Amaleki, Mormon says, “And now I speak somewhat concerning that which I have written” (Words of Mormon 1:3). This suggests that Mormon is speaking about something he personally has already written. He then explains that he has been writing “an abridgment from the [large] plates of Nephi” (Words of Mormon 1:3). As we have seen, the resumptive structure tells us that this (now missing) abridged record had just mentioned that Amaleki “had delivered up these plates into the hands of king Benjamin” (Words of Mormon 1:10). Thus we shouldn’t assume the small plates were Mormon’s only source for things Amaleki spake. Mormon had been abridging the voluminous large-plate record that covered the same period as the small-plate record. According to the resumptive structure, the last event Mormon covered in that (now missing) abridged record dealt with Amaleki. These words in Mormon’s aside appear to refer back to the same passage recapped in the resumptive structure. They tell us that in this missing passage, Mormon had mentioned something that Amaleki had spoken about King Benjamin.

Because we have never read this missing part of Mormon’s abridged record, we aren’t familiar with any of its specifics. On the other hand, we know quite well that in the small-plate record (which replaced the lost text and now, in our reordered Book of Mormon, immediately precedes Words of Mormon), Amaleki mentions King Benjamin (see Omni 1:23– 25). Consequently, when Mormon refers to specific words spoken by Amaleki about King Benjamin, our mind tends to jump to the specific words we remember from reading the replacement small- plate record. But Mormon didn’t include the small-plate record with his own record until after he wrote his aside (see Words of Mormon 1:6). The aside discusses things Mormon himself has previously written. We would have recently read these same things ourselves, just a few verses earlier, if they weren’t missing from the Book of Mormon.

One reason readers of the Book of Mormon have assumed that Words of Mormon was written as an addendum to the small plate record is that the small-plate record appears to supply context and antecedents for the terms these plates and this king Benjamin in Words of Mormon 1:3. The content of the resumptive structure, however, suggests that the missing text that once immediately preceded the heading “The words of Mormon” is the more likely source of the required context and antecedents. In addition, Doctrine and Covenants 10:38–39 suggests that this same missing text [Page 32]described the small-plate account, so it also supplied the antecedent for the term this small account in Words of Mormon 1:3.

The term these plates doesn’t always require an antecedent. In many Book of Mormon passages, the term these plates is used with no antecedent reference to a specific set of plates. In these passages, the term these plates consistently refers to the plates being written upon. (See, for example, 1 Nephi 9:1–5, 10:1, 19:1–5; 2 Nephi 5:4, 31–32; Jacob 1:2–4, 3:13–14, and 7:27.) One such passage adds a brief identifying phrase after the term these plates to confirm this meaning. In this passage, Nephi identifies content being placed “upon these plates which I am writing” (1 Nephi 6:1). He then refers to the set of plates upon which he is writing (the small plates) simply as “these plates” (1 Nephi 6:3, 6). In all of these passages that don’t mention another set of plates, the term these plates refers to the plates being written upon.

Other passages, on the other hand, initially identify a set of plates other than the one being written upon. In these passages, this other set of plates becomes the antecedent for the subsequent term these plates. For instance, Mormon identifies “the plates of brass” (Mosiah 1:3) and then quotes King Benjamin, who refers to them as “these plates which contain these records and these commandments” (Mosiah 1:3), and later simply as “these plates” (Mosiah 1:4). In another passage, King Limhi identifies “twenty four plates which are filled with engravings; and they are of pure gold” (Mosiah 8:9), then refers to them simply as “these plates” (Mosiah 8:19).

I propose that Mormon wrote Words of Mormon as a continuation of his ongoing abridgment of the large-plate record, which he wrote on plates he made with his own hands (see 3 Nephi 5:11), commonly called the plates of Mormon. If Mormon is writing Words of Mormon on the plates of Mormon, then his term these plates, which clearly refers to the small plates, should have been introduced with an earlier direct reference to the small plates. However, in the text of Words of Mormon, Mormon’s initial reference to the small plates uses the term these plates with no antecedent.

This lack of an antecedent has convinced some that Mormon is writing Words of Mormon directly onto the small plates. Amaleki’s last sentence on the small-plates, however, appears to contradict this idea: “these plates are full” (Omni 1:30). Possibly believing that the text of the Book of Mormon offers no viable alternative, creative students of the Book of Mormon have offered some fairly plausible work-arounds. The small plates conceivably could have had margins or other white space into which Words of Mormon [Page 33]could have been inserted, or maybe Mormon added a plate or two to the small plates to accommodate Words of Mormon.68

The resumptive structure in Words of Mormon 1:9–10 reveals a simpler, sounder solution to this problem. This structure shows that Words of Mormon is a continuation of the lost text. Mormon didn’t need to fit Words of Mormon onto the already ancient and already full small plates. He wrote Words of Mormon onto the plates of Mormon in the normal course of his abridgment of the large plates. And he wrote it right after he had written a description of Amaleki’s delivery of the small plates to King Benjamin. However, the loss of the 116 pages of manuscript removed that description (and everything in Mormon’s abridgment before that description) from the Book of Mormon. The resumptive structure recaps that missing description, giving us a glimpse into the final passage of the lost manuscript. The recap in Words of Mormon 1:9– 10 tells us that just before the aside in Words of Mormon 1:1–8, Mormon himself had recently written that description, which mentioned both the small plates and King Benjamin. Therefore, that earlier description of the delivery of the plates had once provided the (now missing) antecedents for the terms these plates and this king Benjamin in the aside.

Other evidence from the Doctrine and Covenants suggests that the same missing passage just before the aside also supplied the antecedent for Mormon’s term this small69 account in the aside. Like the term this king Benjamin, the term this small account presupposes an antecedent — a recent direct reference to the same account. For instance, Mormon’s use of the term an account in Mosiah 28:17 provides the antecedent for his three uses of the term this account in Mosiah 28:18–19. In Words of Mormon, on the other hand, there is no antecedent for the term this small account. Neither is an antecedent for the term this small account found in the book of Omni or the resumptive structure. Fortunately, Doctrine and Covenants 10:38–39 reveals additional content from the lost manuscript. This revelation tells us that the lost text had mentioned [Page 34]“a more particular70 account” (the small-plate account) of things written for the people in our day. This revelation doesn’t tell us, however, just where in the lost text this “more particular account” was mentioned. Indirect evidence, however, suggests that it was mentioned in that same final passage at the end of the lost text.

As we’ve seen, that final lost passage mentioned the small plates. It appears that Mormon learned of the existence of these plates as he studied the large-plate record and wrote that passage, so he then searched for them and found them. Mormon’s search for these plates at that specific time indicates that he did not learn about them — or the small account written on them — before that time. If Mormon had learned about this “more particular account” earlier, he probably would have searched for the small plates sooner. The timing of his search circumstantially suggests that the lost text’s description of this small account, which the Lord mentions in this revelation, was found in the same final passage. It appears, then, that the final passage of the lost manuscript originally supplied antecedents for all three terms (this king Benjamin, these plates, and this small account) found in Words of Mormon 1:3.

As Mormon resumes his abridgment after writing this aside, his words indicate that he is simply moving the narrative forward from the point where it had left off — Amaleki’s delivery of the small-plate record to King Benjamin. The third element of the resumptive structure moves forward with the narrative from this point. First, it mentions that King Benjamin secured the newly acquired record with his other records, all of which later came into Mormon’s possession (see Words of Mormon 1:10–12). It then describes some major events of King Benjamin’s reign.71

[Page 35]Some scholars have suggested that Mormon’s description of these events in Words of Mormon 12–18 reviews events previously described in the lost portion of Mormon’s abridgment. However, when Words of Mormon is read in light of the resumptive structure, Oliver Cowdery’s unique mark and reconstructive edits, and other evidence outlined herein, nothing in the text suggests that Mormon had covered these events previously. Indeed, Mormon’s term this king Benjamin, used three times in Words of Mormon, suggests that Mormon may still be introducing King Benjamin to readers of his abridgment. Thus the final event discussed by Mormon prior to his aside (the delivery of the small plates to King Benjamin) may be Mormon’s initial reference to King Benjamin. The brief manner in which Mormon covers these events isn’t all that unusual and needn’t suggest that he covered them earlier in greater detail. Mormon’s abridgment includes other similarly brief descriptions of similar events that are not reviews of events covered previously. For instance, even though Mormon sometimes describes battles in great detail, he also sometimes mentions major, important battles only briefly (see Alma 3:20–24, 28:2–3, and 63:14–15 and 3 Nephi 2:11–17). Similarly, in two provisions, he touches only lightly on efforts to overcome Nephite contention and dissensions. One was an unsuccessful effort to end “dissensions and disturbances” (Alma 45:20– 24). The other was a successful effort to convince many people to repent (Alma 62:44–52).

4. Mormon’s Choice to Focus the Balance of His Abridgment on Small-plate Prophecies

As explained earlier, many scholars believe Mormon wrote Words of Mormon after all his other Book of Mormon writings.72 However, textual evidence within Mormon’s aside at the beginning of Words of Mormon indicates that an important purpose of this aside is to describe two decisions, one of which affected the balance of his abridgment. After reading the small plates, Mormon was touched by the revelations and [Page 36]prophecies they contained. It appears he wrote this aside primarily to share two related decisions with his readers. One decision was to keep the small-plate record with his own record. The other was to focus the balance of his abridgment on the small-plate prophecies and their fulfillment.

As he describes these choices, Mormon uses several terms that refer (directly or indirectly) to prophecies. In Words of Mormon 1:3–6, he uses the word prophecies only twice, but textual analysis can suggest that several other terms also refer to prophecies. The following highly annotated quotation emphasizes and explains these direct and indirect references:

I found this small account of the prophets [and their prophecies] from Jacob down to the reign of this King Benjamin, and also many of the words of Nephi [including his prophecies]. And the things [prophecies] which are upon these plates pleasing me because of the prophecies of the coming of Christ, and my fathers [who lived after these small-plate prophets, but before me] knowing [and having recorded their knowledge in the large-plate record] that many of them [these small-plate prophecies] have been fulfilled — yea, and I also know [and am adding my testimony here and in the remainder of my record] that as many things [prophecies] as have been prophesied concerning us down to this day has been fulfilled, and [I also know and add my testimony here and in the remainder of my record that] as many [of these prophecies] as go beyond this day [and so will be fulfilled in the future, including in the latter days] must surely come to pass — wherefore [for these specific reasons], I choose these things [these prophecies recorded on the small plates] to finish73 my record [the balance of my abridgment] upon them [making these prophecies the subject or theme of the rest of my record — it will be about them],74 which remainder of my record [the balance of my abridgment] I shall take from the plates of Nephi [the large-plate record]. And I cannot write a hundredth part of the things [doings] of my people [so this thematic focus will emphasize prophecies as I omit much of the history]. But behold [even though only a small record can be passed on], I shall take these plates [this refers to an act that has not already been done but will be done in the future] [Page 37]which contain these prophecies and revelations [the small plates of Nephi] and put them [the small plates of Nephi] with the remainder of my record [the balance of my abridgment], for they [the small plates of Nephi] are choice unto me [because of the prophecies and revelations they contain] and I know that they [the small plates of Nephi] will be choice unto my brethren [for the same reason]. (Words of Mormon 1:3–6)

Two Purposes Filled by the Small Plates. Thus this passage describes the importance of the prophecies on the small plates and tells us that Mormon chose at this time to make these prophecies and their fulfillment the main topic for the balance of his abridgment. This decision, and the emphasis placed on it by Mormon, would make little sense if his abridgment were already virtually finished. On the other hand, if he is recording this choice in the original second chapter of the book of Mosiah, it is a choice that affects all the balance of his writing — everything that Mormon wrote that was not lost. (Both his statement about choosing the small plates as a source of influence in his future abridgement, and his statement about adding the small plates to his work, point to future events, whereas they would be completed acts under the traditional view of Words of Mormon being written at the end of Mormon’s work.) It would appear, then, that the Lord’s purpose in preserving these prophecies on the small plates was not only to use the small-plate record as the “first part” of the Book of Mormon, but also to inspire Mormon to focus all the remainder of the Book of Mormon on the fulfillment of these important prophecies.

Logical Inconsistencies. In this passage, Mormon discusses two concepts that can easily be confused. His term these plates refers to the small plates. His separate term these things refers to the prophecies on the small plates and not to the plates themselves. Some students of the Book of Mormon nevertheless maintain that when Mormon states “wherefore I choose these things to finish my record upon them” (Words of Mormon 1:5), the words these things refer to the small plates. Or perhaps, since the small plates were already full (see Omni 1:30), they suggest that these words refer not only to the small plates themselves, but also to an additional plate or two that Mormon may have appended to the small plates.75 That suggestion, if true, could support the view that Words of Mormon was written upon the (perhaps augmented) [Page 38]small plates and was among Mormon’s final writings. That suggestion, however, gives rise to two logical inconsistencies.

The first logical inconsistency arises because that suggestion is incompatible with Mormon’s use of the word wherefore. The role of this word is to introduce “a clause expressing a consequence or inference from what has just been stated.”76 So when Mormon says, “wherefore I choose these things to finish my record upon them” (Words of Mormon 1:5), he is telling us that he chooses “these things” for a reason he has just mentioned. He has just used the word things to explain that the prophecies written on the small-plate record (the things which are upon these plates) please him because they are true. It would appear that these same things, the prophecies on the small plates, are the intended antecedents for the term these things. Mormon has just stated two clear reasons for making these prophecies the main subject of the balance of his abridgment (they please Mormon and they are true). On the other hand, nothing just stated provides any plausible reason for choosing to write anything upon any specific set of plates.

The second logical inconsistency arises for a different reason. If the words these things refer to the small plates, then the term the remainder of my record has two opposing meanings in two consecutive sentences. Thus the term the remainder of my record, as used in verse 5, would refer to a record written upon the small plates, while the identical term, as used in verse 6 without distinguishing context, clearly refers to something separate from the small plates, to be kept with the small plates.